Mini en Mai Recap Part 3

Overcoming exhaustion and completing the race

On the afternoon of 19 May, I approached the Plateau de Rochebonne on a port jibe. This was two days after starting the Mini en Mai race and a full 24 hours without a functioning autopilot.

The Plateau de Rochebonne is bounded by four marks and about eight nautical miles long. I rounded the first of these marks at 1500, then headed east for about 50 nm towards Île de Ré and La Rochelle.

The next few hours were the high point of this race for me on Terminal Leave. With the Code 0, a reefed jib, and full main sail, the boat was powered up on a reach in about 15-18 kts of wind. We were averaging boat speed over 8 kts for most of the afternoon. Eventually I began to feel the fatigue from the physical requirement of driving tight reaching angles and trimming the mainsheet for most of the day. My arms were sore and the strength of my hands was fading. By the time the Island came into view, most of the competition I rounded the previous set of marks with were just little specks on the horizon behind me. This was the confidence boost I needed and fueled me going into another long night.

As the darkness from the evening set on the fleet, I approached the south eastern edge of Île de Ré and rounded it to port in shallow water. At this point, the tide had turned against the fleet and would remain ebbing for at least the next six hours.

Screen shot of an online Navionics chart after the race (not allowed when racing)

From this rounding point to crossing through the fixed bridge that connects the island to La Rochelle, it is only 2.5 nm. Now we were sailing upwind with a softer evening breeze and at least one knot of current against us. The significant amount of seaweed in this area kept slowing down the fleet. Taking the boat hook to clear the rudders every few minutes, made this task much more difficult without an autopilot to hold my course. [Side note: I heard after the race that one of my competitors ran into so much seaweed here that he was stuck in place. He finally resorted to tying himself to the boat with his climbing harness and diving into the dark water with a head lamp and knife to free the boat. ]

As the adverse current increased, the wider our tacking angles became. Minis are difficult to quickly tack and build speed without losing gauge on the course. The current and shallow water compounded this challenge. If you were following along on the YB tracker, it did not accurately display short tacking while racing. Below you can see a screen shot from my GPS route where I tacked 17 times on this short leg.

A challenging 2.5 nm of sailing upwind towards the bridge connecting Île de Ré to La Rochelle

In addition to the adverse current, this all took place at night. It was a dark night, but light from the moon and the harbor lit up certain areas. The contrast of light and shadows, coupled with sleep deprivation, started playing tricks on my eyes. It was difficult to judge distances and see navigational buoy lights. I had made it a few hundred miles just fine, but now I was concerned about running aground and hitting rocks. Which could take me out of the race and could have halted the rest of the season due to major structural damage.

As I weaved in and out of the channel, got lifted and headed, puff on then a lull again, drift and dodge seaweed…. another black cloud approached. The temperature dropped and the wind died.

Then the lightning started.

Flashes streaked across the sky briefly lighting up the entire harbor and the fleet. Heavy rain poured as I was only about 200 meters from the bridge. There were at least four other boats around me that I was trying to avoid as the visibility decreased from the squall. Judging the port tack layline to make the mandatory bridge channel span was difficult in the darkness as the wind direction jumped around, shoals lined the waters edge, and the current kept trying to pull the boats backwards.

After narrowly missing a bridge span due to the ripping current, I finally made it under the bridge around 0200 that morning. Now I was the lead boat and become confused about where exactly to go. I was trying to navigate using a paper chart on deck, with a heavy rain, at night, and still hand steering the entire time. This body of water is by far my least favorite that I have sailed in France. I didn’t like it last year when I sailed through for the thousand mile qualification route and once again did not enjoy it this season. North of Île de Ré is bounded by land, is very shallow, and filled with mussel traps. As a reminder, we do not have chart plotters (like the charts I am showing now) on our boats. We are required to use paper charts with lat/long provided by a GPS to determine our position.

As I adjusted to this new challenge after the bridge, one of the competitors got on the radio to say they had just sailed through here last week. A few of us got in a line and followed her path. I was now the trailing boat and just as the little fleet took off, I snagged a big pile of seaweed. Going half my original speed, I tried to keep up with the boats while also dislodging Terminal Leave’s rudders from the seaweed. As the lights of my competitors got farther away, I had to rely on following their zig zagging course through AIS to avoid the hazards. The AIS display on deck is part of my VHF radio handset, so it is very small and not detailed. However, I managed to have just enough information to keep me clear of the obstacles and shoals.

Hyper focused and surviving on adrenaline, I kept sailing throughout the night/early morning. Over the next few hours, I would struggle to stay awake. Countless times I would open my eyes, still driving, unsure of how long I might have closed them. A few unexpected tacks woke me up as well.

When I was awake at the helm, the multiple days of sleep deprivation continued to affect what my eyes were seeing. Sailing around mussel/fish traps with red blinking lights and a hazy fog hovering over the water, it felt mythical and out of this world. Little fishing outboard powerboats were driving around with white headlights in between the traps making navigating even more difficult. In the moment, I just could not imagine who these people were or what they were doing out here at that hour. For all I know they were either doing their daily runs or trying to notify the 100 Minis sailing by to stay away. At one point, I saw what looked like a wooden structure appear out of the mist. With the soft glow of a red light, I could see people going up and down the stairs clearly working on something. Was I hallucinating? Maybe… In retrospect, I am pretty sure this was a fellow Mini with a headlamp on coming up from down below. Regardless, I tacked to avoid what might be an obstruction.

Passing by the final mussel trap, I looked back, the mist lifted, and everything looked so clear behind me. I could see the large “X” shaped warning lights signaling vessels about the navigational hazards of the area we had just sailed through. As first light approached, I could feel the weight of exhaustion hit me. My body started to shut down and refused to stay awake any longer.

There were two main reasons to stay awake as I left the narrow channel and exited between the northern side of the island and the coast. First, on my current heading I was about 2.5 nm from a point of land with a flashing light indicating the danger. If I overslept, I could wake up to the noise of the boat crashing into rocks. Second, every time you sleep, boats pass you. I was with a pack of boats and worried when I woke up, no one would be around to race against. You are always faster when competition is in sight.

However, I had succumbed to my body’s sleep deprivation and its ability to stay awake any longer. I had not slept since the one nap about 24 hours previously. It was time to do something to recover. As the wind lightened with the approaching sunrise, I hooked up the back up autopilot, dropped the jib, and eased out the mainsail. I hit my low point of the race, because I felt like I was giving up. I justified slowing down to myself by thinking sleep was more important so I could at least finish the race. Above all else, I had to complete the race to get the race miles credit, but felt like I was giving up on the competition for a nap. Everyone would surely pass me and take off across the horizon. I was frustrated about the autopilot failure, exhausted from the lack of sleep, and disappointed with myself for not being able to stay awake any longer and beat the boats around me. This was the low point and the weight of that thought crushed me emotionally. Going below to briefly lie down (still wearing my gear) felt like I was giving up.

Less than 15 minutes later I was wide awake, no need for a second nap. It is incredible what the human body is capable of during stressful situations. To my surprise, there were about a dozen boats all around me! I wondered if the wind had died or if everyone else hit their breaking point and slept too…either way it did not matter. A wave of competitive excitement overcame my exhaustion and I was back to racing. Up went the Code 0, then the A2 spinnaker with a wind shift. Within an hour, the breeze rotated and we were beating up wind. I was back in this race!

This inset box represents all I can see on AIS of the fleet while racing

Terminal Leave with a reefed main in 20+ knots of wind

Even though I was back in the race, I knew I was not doing well in the fleet. While that was disappointing, all I could do was focus on the current situation. I did everything possible to sail faster and point closer to the wind than my competition. Terminal Leave was handling great and we started passing boats. Over the next few hours, the wind increased and the swells grew in height. As we headed offshore for this 80+ nm upwind leg, the wind velocity increased over 20 kts. After reefing the mainsail, the boat felt more balanced while navigating the waves. About half the day was spent on starboard tack, then the other half on the long port tack up the coast.

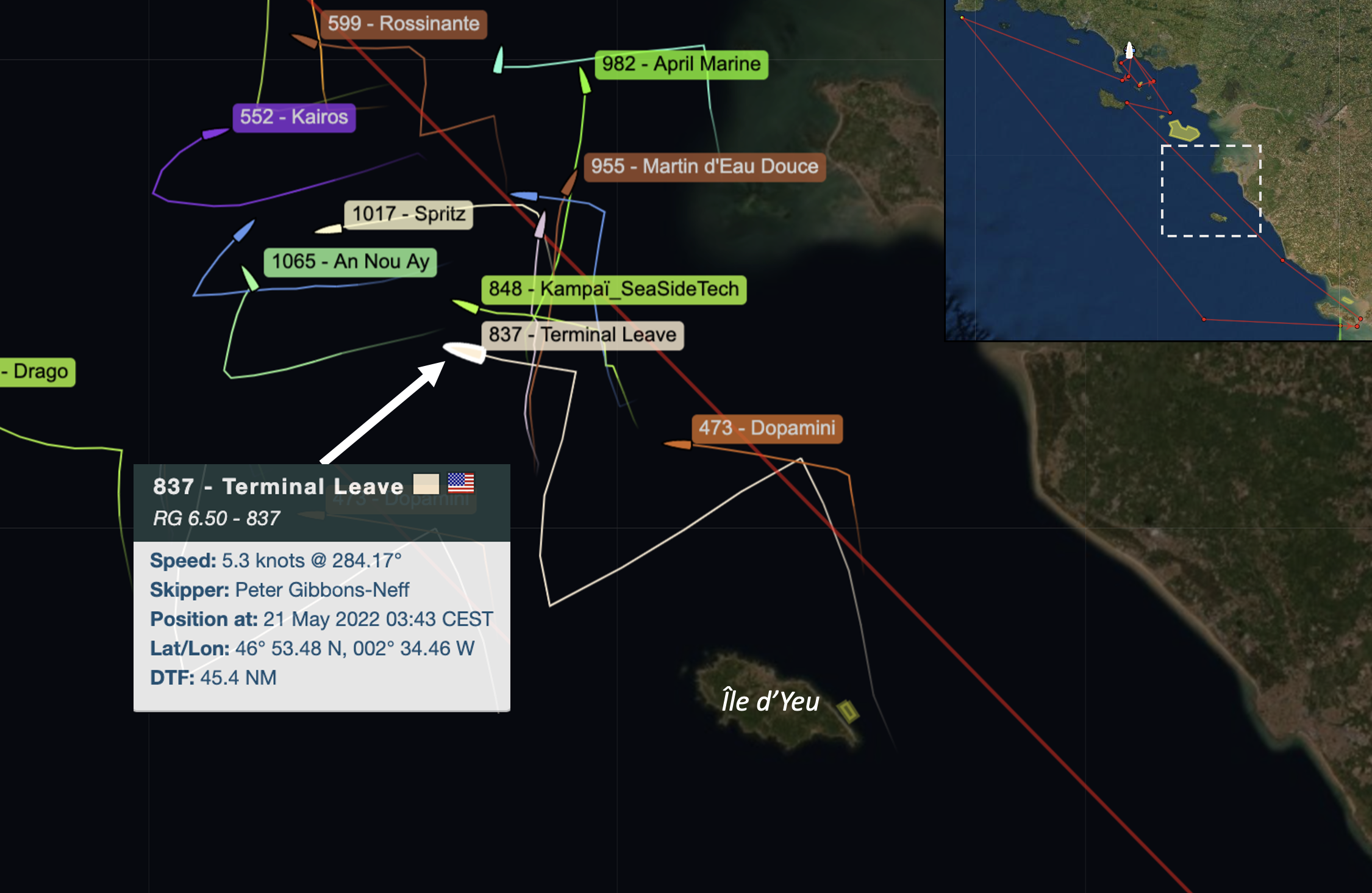

As evening approached on day four, I was sailing between the mainland and just off the eastern coast of Île d’Yeu. Throughout the day I was focused on doing everything I could to maximize boat speed and play the shifts across the course. I continued to do so that night as well, while avoiding rocks in the shallow water along the coast.

Late that evening, the wind softened and the water became flat. The perfect opportunity to catch up on some sleep. The backup autopilot still could not handle the conditions, but I did not want to slow down. With the calmer seas, I was able to balance the boat with sail trim and the wind angle, allowing the boat to maintain an upwind heading. The tiller would naturally make little adjustments to keep Terminal Leave on an acceptable track. Finally!!!! I took a few back-to-back naps, each lasting no more than 12 minutes. This is to maintain a proper look out and avoid fishing boats which are far too easy to find this close to shore. Of course, some naps were cut short when the boat would become unbalanced and unexpectedly dart off course.

The following morning, the boats began to converge on the south eastern shore of Belle Île. By rounding this mark of the course, the race was close to being complete. As we sailed this “z” shaped part of the course, it was just off the wind and became a drag race to the finish with no opportunities to pass.

Around noon on 21 May, I rounded the final mark of the course. Now I just had to sail twenty miles upwind with the finish at La Trinité-sur-Mer. This leg felt like it took forever. Halfway through, the wind completely shut off causing this part of the fleet to drift for a few hours, while most of our competitors were finished and docked at the port. The afternoon sky was clear and it became very hot as we floated, not moving for what felt like an eternity.

Finally, the late afternoon sea breeze filled in, allowing us to start moving again, especially since the tide had turned against us. In the final two miles of the course the wind increased into the high teens, the temperature dropped and waves were splashing across the boat, I was completely soaked.

I was beyond the point of exhaustion right now. I needed to finish this race. Even though the time limit had not been reached, the race committee that ran the finish line started packing up during my final approach. Part of me was concerned I had surpassed the time limit (no way of knowing at the time). I also thought I was in last place because I did not see anyone else behind me. It was a demoralizing way to finish the race, compounded by the fatigue.

At 1926 that evening, I crossed the finish line. 4 days, 7 hours, 40 minutes and 12 seconds. Out of 100 boats in the race, 80 were series boats that I was competing against. I finished 68th and most importantly, I completed the race.

Hand steering the boat for over 78 hours certainly was not ideal, but Terminal Leave and I persevered. It was the test I needed to learn my boat better. This highlights why the required minimum race miles to compete in the Mini Transat are so valuable. Despite the challenges, I am grateful it happened during this race and not half way across the ocean. I am always learning something new and making little improvements each day.

Thank you for reading this blog post, I hope you enjoyed hearing about my experience in the Mini en Mai race. If you liked it, please share the blog post with your friends and family and encourage them to follow this campaign.

Thank you for your support!

This racing is only possible with donations from supporters. Want to help my mission to race in the Mini Transat to raise awareness for U.S. Patriot Sailing? Please donate through my GoFundMe page here:

Thank you to my sponsors and supporters for making this possible!